Do Rocks Have Desire?

Renewable Historicism,

Coleridge’s “Outness” of Mind,

and Peircean Biosemiotics

© This paper is not for reproduction without the express permission of the author.

The body

Eternal Shadow of the finite soul/

The Soul’s self-symbol/its image of itself,

Its own yet not itself

Coleridge, ? 1810, from manuscript

Only by acknowledging “the action of kindred souls on each other” (C[oleridge’s] L[etters], 2.1197), the fact that other beings modify our thoughts, will an individual attain self-consciousness and behave morally toward others.

From Coleridge and the Concept of Nature, by Raimonda Modiano

Language & all symbols give outness to Thoughts / & this the philosophical essence & purpose of Language

Notebooks, 1.1387, S. T. Coleridge

Eyes seeking the response of eyes

Bring out the stars, bring out the flowers,

Thus concentrating earth and skies

So none need be afraid of size.

All revelation has been ours.

From “All Revelation,” by Robert Frost

1 Objectives

Theresa Kelley writes that “if it is possible to show, via the work of [John Clare and Charlotte Smith], how botany is part of the material and philosophical ground of Romanticism, then we may be able to extrapolate from these and allied instances models for a Romantic binding of mind and world” (4). Indeed, it is our purpose here to extrapolate from just such “allied instances” eighteen models (or, rather, three or four models and their various permutations) of a “Romantic binding of mind and world.” Professor Kelley also speaks of the critical interest that the philosophical inquiry of Hilary Putnam, Martha Nussbaum, and other recent critics and philosophers has “for imagining Romantic interiority as allied, perhaps even formally allied, to a material reality that has long been regarded as its Romantic ‘other’” (4). While rejecting as does Kelley the binarism of self (“Romantic interiority”) and “other” as well as the view that “mind or world are reducible to each other” (4), we present our Romantic models of the formal yet material alliance of mind and world as an exercise in imagining/imaging—again allowing Kelley to situate our study—the “productive irreducibility that sustains Romantic subjectivity at a moment in cultural history when the signs of materiality were very much ascendant within the cultural sphere or spheres” (4).

Our heuristic models or pictograms derive from Samuel T. Coleridge’s theory of the symbol, from the semiotics of Charles Sanders Peirce and Julia Kristeva, and, to a lesser extent, from German Naturphilosophie and present-day ecological theory. There exists, of course, an understandable bias toward formal models, but we claim that models like ours—based on the open-ended triads of Coleridge and Peirce instead of on the closed binary oppositions of logocentrism—rather than fixing categories and oppositions, demonstrate how formalisms need not be disembodied and prescriptive abstractions that are normalizing or idealizing in their function; rather, formalisms, our models illustrate, can have a heuristic function as well as a materialist (a situated) basis. In other words, through our modeling of Coleridge and Peirce, we attempt to renew our understanding of the relationship between “formal” and “material” as part of our larger goal of renewing our understanding of the relationship between interiority and exteriority.

Our models, then, are part of what F. Elizabeth Hart calls “a materialist linguistics,” wherein

Forms emerge from the subject’s material conditions through the mediating presence of a semantic system, a system whose rootedness in the material cognitive system closes the formalist gaps between content and structure, subject and system. (328)

Our models of this “material cognitive system” are predicated on a belief that thoughts are not ideas that are inside our heads and therefore self-evident—“ideas” as conceptual antecedents in an endless referential round of signification between signifiers (words) and signifieds (concepts)—but, rather, that thoughts are signs that are external to the self and, therefore, “Other”-evident (e.g., “We hold these Truths to be ‘Other’-evident . . .”), “Other”-evident in the sense that thought-signs are both constituted by, and, especially, constitutive of the Other. Thoughts, that is, are special kinds of signs not reducible to the “sign vehicle”-“meaning” dyad and its many permutations from Augustine to Goodman; rather, for Peirce and Coleridge, thought-signs (“Interpretants” for Peirce and “Symbols” for Coleridge) are outcomes, responses, or effects (emergent and thus not capable of being encoded until after thought has happened) that mediate (ratify or validate) the conditions of their own production. Thoughts considered as signs, that is, as Interpretants or Symbols, contribute to the actual emergence or unfolding of the world of sense and undermine the signifier-signified pair’s autonomous or hegemonic relationship to thought. Thus meaning is not circumscribed merely by reference; rather, unpredictable response constitutes the cognitive and environmental relationships within which reference “makes sense”—“making sense” understood both as making concepts and making a world that is capable of being sensed. In these senses, then, Coleridge like Peirce held that thought was, as we would say today, an environmental phenomenon. Thus, our models illustrate, as Coleridge charged himself with describing, how sense is derived from the mind (not how mind is derived from sense, the Hartleyan or Lockean view) AND how objects, both immediate objects (or concepts) and dynamnic objects (or experienced things—even the Kantian Things-in-themselves) grow under the sway of the Peircean Interpretant or the Coleridgean Imagination or Symbol and thus become more and more real. But this is precisely what Thomas McFarland tells us about the role of the symbol for Coleridge. In “Involute and Symbol in the Romantic Imagination,” McFarland writes, “the task here is to show that the structure of the symbol, considered not as an indicator of wholeness [an “indicator” being a mere referential or signifier-signified relation] but as a response to [an Interpretant of] the experience of reality, has a rationally cognitive validity. Symbol, far from being a mystification, is a direct accounting of human perception [emphasis added]” (51-2). That is, for the Coleridge of McFarland, “response” (significate outcome) not “indication” (reference) is the key to materialist cognition.

The above discussion serves to characterize mind as an environmental phenomenon. Of course, though neither Peirce nor Coleridge uses the term “environmental” when discussing mind or consciousness, the characterization is nonetheless apparent. C. S. Peirce writes,

the psychologists undertake to locate various mental powers in the brain; and above all consider it as quite certain that the faculty of language resides in a certain lobe; but I believe it comes decidedly nearer the truth (though not really true) that language resides in the tongue. In my opinion it is much more true that the thoughts of a living writer are in any printed copy of his book than that they are in his brain. (CP 7.364)1

We here echoes of Peirce’s semiotic model of cognition, wherein thoughts are signs whose locus is not exclusively in the mind, when Coleridge writes,

Ah! Dear Book! Sole Confidant of a

breaking Heart, whose social nature compels some outlet. I write far

more unconscious that I am writing, than in my most earnest modes I talk—I

am not then so unconscious of talking, as when I write in these dear, and only

once profaned, Books, I am of the act of writing—So much so, that even in the

last minute or two that I have been writing on my writing, I detected that the

former Habit was predominant—I was only thinking. All minds must think

by some symbols— . . . —which something that is without, that has

the property of Outness (a word which Berkley preferred to

“Externality”) can alone fully gratify…(Notebooks 3.3325)2

Our models, then, attempt to represent thought and material signs (the property and process of the “Outness” of mind) as engaged in the ongoing and inherent creativity of life and language (Kristeva’s “semiotic”) rather than as passive objects of phallogocentric discourse (Kristeva’s “symbolic”).

In the context of the Kristevan “semiotic,” we note that Coleridge himself alludes to (what we would call) semiosis as a phenomenon that pervades all natures (human and otherwise) when he writes in “The Statesman’s Manual” of the potential parallels of plant phototropism and thought: “O!—if as the plant to the orient beam, we would but open out our minds to that holier light” (“Appendix C” 73). Peirce also discusses this relation of thought (as signs) to the signing actions (phototropism) of a flower:

A Sign is a Representamen with a mental Interpretant. Possibly there may be Representamens that are not Signs. Thus, if a sunflower, in turning towards the sun, becomes by that very act fully capable, without further condition, of reproducing a sunflower which turns in precisely corresponding ways toward the sun, and of doing so with the same reproductive power, the sunflower would become a Representamen of the sun. (CP 2.274)

What we attempt here, then, is to take seriously the task of describing in (eco)logical terms what Coleridge means when he speaks of the “opening of our minds” as does “the plant to the orient beam” or what Peirce means by the signing action of the sunflower. Further, we shall illustrate, if mind is not in the brain, then our Peircean category of thoughts-as-material-signs-that-are-Other-evident subjects all objects (Others) to subjectivity as partners in the evidentiary process, hereby undermining the relentless duality of the subject-object and interiority-exteriority binaries. Indeed, though our models are not interactive in the received format in which they must be viewed by readers here, the particular point that we would hope these models would illustrate, that even rocks are mindful subjects subject to desire or intentionality, represents a commitment to what is, according to our naturalization of Kristeva’s semiotic, a fundamentally erotic and interactive ecology of mutual signification, as our own obsessive playing with the colors and forms of the models represented to us the erotic intentions of the graphemes themselves. Indeed, for us the models had an intention of their own and we just enjoyed playing the roles they never fixed but seemed only called out of us.

We seek, then, through the diagrammatic logic of our models,

1. a realist solution to the problem of how sense may be derived from the mind;

2. insight into the constitutive power and phenomenology of the pun, an idea that permits us to interpret the great web of being of the Naturphilosophen in both ecological and cognitive terms;

3. an “environmental” view of mind or cognition predicated upon Coleridge’s “outness”; and

4. an understanding of intentionality not only as a conscious process but also, in Edwina Taborsky’s words, “as the absolute requirement of an entity for ‘reaching out,’ for contact with Otherness.” “I think it’s a mistake,” writes Taborsky, “to consider intentionality within the framework of meaning that we have, in our ‘western’ minds, grown up with, i.e., the ego-centered, author-centered, monologic meaning” (1).

In addition to the four just-mentioned conceptual contours of our essay, we hope to meet the following objectives,

1. To show how when interpreted in the light of Peircean and Kristevan semiotics and modern community ecology, Coleridge’s theory of the symbol takes on a fullness, even a completeness, that it is often denied. To this end, we shall

a. Compare in some detail Peircean and Coleridgean semiosis (though Coleridge had no such all-encompassing term)

b. Play with, in the spirit of Peirce’s existential graphs and Coleridge’s own interest in modeling dynamic systems, a diagrammatic logic which, while confined by the universe of the mere page or screen, takes on a logical life of its own and thus partakes of the logic of thought, Peirce’s object being, as Beverley E. Kent writes, “to have the operation of thinking literally laid open to view—a moving picture of thought” (qtd in Brent 292).

c. Represent mind or thought in the Peircean and Coleridgean senses, that is, as we might say today, as an environmental or community—rather than uniquely individual—phenomenon. To this end, we present an illustration of how Peirce’s “objective idealism” or “Ideal-Realism” might work, an illustration, that is, of his view that “Mind (the Real) is itself or through the agency of the sign both immanent and transcendent in the world of nature” (CP 8.186, qtd in Brent 344).

5. to show how a Romantic or phenomenological ecology can include, as Malcolm Nicolson writes in the context of the science of Alexander von Humboldt, “emotional and aesthetic responses to natural phenomena . . . as data about those phenomena” (180); and,

6. to show how an object such as a rock can exhibit intentionality to the extent that by getting itself written into biological, aesthetic, and legal codes it transforms itself into an objective and thus secures its own survival.

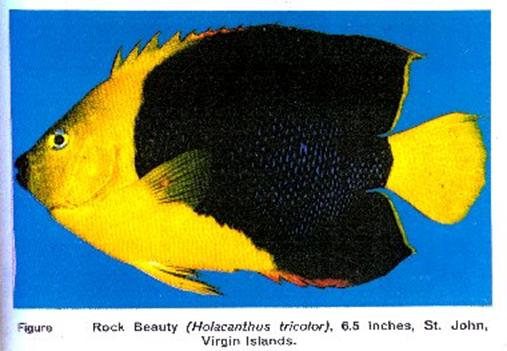

The models presented below in Figures 1-14, then,

establish the Peircean and Coleridgean bases of a semiotic theory or a Romantic

science that furnishes a way of reading the textualized body of the Caribbean

reef fish Holocanthus tricolor, the Rock Beauty (Figures 15 and 16), a

way of reading that undermines Enlightenment ideas about intentionality. The

last two models, Figures 17 and 18, in the context of (a) Coleridge’s

“Thingification,” “Punning,” and “Desynonymization,”3 (b) Peircean

semiosis, and (c) Naturphilosophie, represent in (eco)logical terms what

Michael Shapiro describes in linguistic terms as the “telos of

diagrammatization” (17 and passim), that is, the fact that objects

can spin objectives out of themselves within the semiotic webs of life

and language that constitute the biosphere and semiosphere. Objectives are

latent in all objects. Indeed, Coleridge connects “objects” to “objectives,”

linguistically capturing this emergence, in his own visual “pun,” one that

results from his (inadvertent?) erasure or crossing out of part of one word

only to reveal two words simultaneously: as Coleridge writes, “The Objectives

of the Sense are collectively termed phænomena”(Notebooks 3.3605).

We conclude our discussion of our own objectives by situating our models in the context of Naturphilosophie. Raimonda Modiano’s characterization of Schelling’s philosophy of nature describes very well what our primarily Coleridgean and Peircean models hope to illustrate: Nature’s self-organizing nature:

In the process of self-knowledge, the Absolute objectifies itself in particular things, forming the world of nature, then perceives itself as pure subjectivity and as the source of all production, and finally comes to recognize its essence as the identity between the subjective and the objective, self and nature. The Absolute thus expands itself into finite objects only to gather back into the infinite. Nature is the form by means of which the Absolute acquires “outness” and knows itself through another; it is a symbol of the Absolute which, “like all symbols, takes on the independent life of that which it signifies.” Nature is both real and ideal. (162)

Although Coleridge was never at all comfortable with the theory of the self-organizing nature of Nature championed by the Naturphilosophen, as we show below, in a present-day semiotic context, Coleridge’s dynamic theories of language growth and of the mind (which do owe much to Schelling’s theorizing) provide a framework within which to describe in no little detail the way in which even inorganic nature, e.g., a rock, “like all symbols, takes on the independent life of which it signifies.” When seen in the renewable contexts of Peircean semiotics and modern evolutionary ecology, Coleridge’s theory of the symbol allows for a new articulation of interiority and exteriority, of organism and environment, of self and other, one that is so often spoken of today but which is rarely if ever convincingly exemplified. This paper, then, is one extended example of the desire and writing ability of rocks.

2 Methodology

For the Naturforscher of German Romanticism,

The history of nature and the history of knowledge are immanently connected. For the Romantic Naturforscher, however, history is always more than the gathering and rendering of facts—essentially history means the interpretation of the past in the light of ideas and the linking of it with the present and the future. The history of nature and the history of knowledge about nature have a common origin, have passed through a separate development and are heading towards a common future (von Engelhardt 55)

Indeed, as we shall demonstrate, the method of literary history and criticism that we shall employ in this essay, a pragmatic sort of criticism that we are calling “Renewable Historicism,” is one that represents here an attempt to interpret Coleridge’s ideas by linking them with “the present and the future.” When applied to Coleridge, Renewable Historicism, although we have not space here to present anything more than a sketch of its meaning, is not so much concerned with recovering the situated meaning of his ideas in his time and place or with revealing how his texts bring about or reproduce the very history of which they purport merely to be artifacts (important tasks in themselves). Rather, Renewable Historicism seeks to renew or recover old (or new) texts in terms of explicit values we (it is embarrassing to admit) choose as necessary for the sustainable communities we imagine for the future.

For New Historicists history is a text that needs to be interpreted, not a “set of fixed, objective facts” (Abrams 183). Similarly, though working in the opposite direction, for Renewable Historicists, the future is an “interpretant” that needs to be historicized, that is, subject to both conscious and unconscious selection by human and natural communities and thus given a chance to be history later. If values are goals our behavior strives to realize, interpretants are those value-striving behaviors or responses, though they must be understood as operating in a frame not necessarily of goal intention but rather of goal direction: an interpretant, then, is, in Peirce’s phrase, the “proper significate outcome” of any signing-action or interpretive act other than mere reference—“proper” only in the etymological and phenomenological sense that a given outcome is “one’s own” (Latin propius), that is, and always in retrospect, that we give a given outcome a particular value within our Umwelt or lived world. As Vincent Colapietro writes,

The Interpretant is not any result generated by a sign. Something functioning as a sign might produce effects unrelated to itself as a sign; for example, a [signal] fire indicating the presence of the survivors of an airplane crash might set a forest ablaze. The forest fire would be an incidental result and thus not an interpretant of the sign calling for help (or indicating the whereabouts of the survivors). (122)

One “proper” significant outcome would be “rescue,” not the loss of a forest resource, although interpretants may be infinitely generated, viz., a forest fire, the death of animals, the loss of homes adjacent to the forest, a chuckle in Chicago about the supposed superiority of California living (“first fire; what next, mud slides!”), the heroic act of a forest-fire fighter, the death of the same, a lonely spouse, his or her decision to go back to college now that she or he is alone, and so on. Renewable Historicism, as we shall see, combines literary criticism and creative writing (thus we also call it “ficticism”) in its management of and concern for the production of “proper” outcomes as a result of the critic/writer’s interference in the emergent causal network.

What follows are three brief examples of how texts are approached in Renewable Historicism.

1. There is a class of metaphor defined by the fact that it no longer means the same thing to us as it did to earlier readers but which continues to work as metaphor albeit with new meaning. Take Shakespeare’s “salad days,” which for Elizabethans meant those “days of youthful inexperience.” For many first-time, present-day readers of Shakespeare, “salad days” has become a metaphor that has a new vitality and a new object or referent in the context of our culture’s concern with personal health, diet, and ecology. This new vitality, of course, is only tangentially related to the original meaning of “salad days.” Interpretants, such as the new meaning of “salad days,” have a creative force of their own. But Renewable Historicist relationships of persons to texts can instigate as well as ride the wave of a linguistic sign’s self-organizing capacity.

Raimo Anttila appears tacitly to assume that the evolution of language or (literature) and the evolution of nature are contiguous when he uses biological metaphors to describe linguistic change: “This is general in evolution. Units adapt to their environments by indexical stretching to produce an icon of the environment” (43). The meaning of “salad days,” then, is in the process of being stretched or re-figured, as, in an evolutionary context, the meaning of O2 (itself a meaning bearing figure and a by-product of photosynthesis) was re-figured by respiration: that is, oxygen, once deadly, was contextually re-figured so as to make ecological sense in terms of respiration (evolution’s new reader). As the story is told in the biological sciences, the evolution of photosynthesis (the major producer of O2 in nature) is based in part on the “stretching” or mutation of the heme molecule: chlorophyll, then, is a mutated heme molecule. Hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying molecule necessary for respiration, is itself a permutation of the heme molecule. Thus, in a kind of biological poetic justice or irony, the “stretching” of the heme molecule is fundamental to both the introduction of deadly oxygen into the atmosphere (through photosynthesis) and the later evolution of an oxygen-transport strategy (transport/carry across/metaphor) (through respiration) that offered a way around the dilemma of deadly oxygen. The heme molecule, then, is a scheme-atic or biological metaphor. However, some figures of speech/molecules/species seem to lack the potential for reinvention and become, in essence, extinct. Take, for example, the rather common expression from Shakespeare, “Take me with you,” which, to the Elizabethan reader, meant “Make yourself clear.” This figure, rather than having been re-figured, seems to produce only confusion (so far anyway). An interpretant, in this context, then, would not be the old meanings (the signifieds) of “salad days” or of “take me with you” (the signifiers) but emergent (unpredictable) meanings or “outcomes” as determined by the telic force of diagrammatization residing in the signifiers themselves and their environments, including its triangulation through human presence.

2. The relationship of Lisa Freinkel’s play Hamlette, a feminist and radical adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, to that older play generates out of itself a set of interpretants just as “salad days” exhibited a tendency to be reinvented or adapted and thus to maintain its vitality (that is, to produce new ideas in new readers’ heads in new contexts). According to Freinkel,

[T]ransforming Hamlet into a female is not such a great stretch [read: “This is general in evolution. Units adapt to their environments by indexical stretching to produce an icon of the environment”] and [my] changes have altered the narrative “surprisingly little. Shakespeare is so capacious you can really deform his words and still end up with a play that looks pretty much like what he wrote. If you think Hamlet is a play about mortality and about humans coming to terms with the limits of rational thought, [Hamlette] is the same play. If you think this play is a play about relationships between children and their parents, it’s the same play.” (Agatucci and Joiner 10)

It is this capacity to be re-invented, to be the same and other, this self-organizing agency of material language—akin to Coleridge’s desynonymization and punning—and the capacity to discover and to shepherd emergent possibilities (as does Freinkel) so as to make whole plays and puns (Hamlet/Hamlette) seem inevitable or ordained that constitute the forms and functions (and the goals) of Renewable Historicism.

3. In the context of the difference between the literary criticism of interpretation and that of the interpretant consider the following: through interpretation we can understand how the genres of tragedy or pastoral may reproduce the values they embody in subsequent generations, such as pastoral’s hypostatizing of the value of nature as primarily that of a humanized place, whereby the word “nature” comes to mean a dimension of human nature; the interpretant of the pastoral genre, however, is not the commentary on the genre but the accumulative effect of habitat depletion that a commitment to a pattern of interpretation helps produce or the way in which the readers or writers of pastoral orient themselves physically to the world. These simultaneously nonliterary and literary effects are examples of interpretants. And thus, as Joseph Meeker writes, some genres have more or less survival value as biological adaptations for humanity and the natural and human communities of which they are a part. These interpretants, then, are energetic, emotional, or logical outcomes that are not necessarily reducible to referential meaning/interpretation. Interpretants are created by and also act upon and interact with those historical texts and their subsequent interpretations that serve to bring about or reproduce the very history of which they purport merely to be artifacts—thus accounting for the history (future) of history. As soon as we engage in interpretation, we consciously circumscribe (and appropriate to the human and rational) the function of criticism thereby undermining the agency of non-conscious entities, effects, and outcomes (interpretants), That is, interpretants cannot be reduced to the relationship of signifier (the interpretation) to signified (history as text) but rather generate outcomes (separate from mere reference) that do not merely reproduce themselves and their culture but mediate those reproductions as environment does the expression of the gene code—thus making alternative futures possible.

The goals of “Renewable Historicism,” then, are two: (1) to play with thought-signs in such a way as to encourage their detachment from their referential objects and thereby increase their chances of escaping one (perhaps encumbering) context so as to be transformed by later (and perhaps more amenable) contexts; that is, to find those thought-signs, in Coleridge say, that are rich with potential for re-valuation, and (2) having discovered or encouraged new combinations of thought-signs, to create an explicitly value-based status for some of these renewable or recyclable thought-signs so that they may contribute to a sustainable cultural praxis. Thus, we adapt (rather than adopt) the Coleridge of other critics.

Finally, as we shall see, Coleridge’s theory of the symbol as we have come to understand it, in that theory’s environmental and cognitive dimensions, would not be possible except through Peirce; indeed, Peirce is, for us, constitutive of Coleridge, though what is constituted can’t be said retrospectively to be anywhere but in Coleridge. Coleridge renewed is Coleridge re-situated in our conscious re-valuation—as O2 was re-figured by its new reader photosynthesis.

That Coleridge’s theory of the symbol has been for some time in need of re-figuration is made evident in Kathleen Coburn’s great edition of the Notebooks. She writes, about a passage we cite below, that

Coleridge’s term [Empiricism] did not catch on, even with himself. He so quickly moves here . . .that we are lost in his labyrinth and pulled out suddenly . . .to “recompense” what is now dubbed the Theory of SYNCRETISTS. . . . The terms employed here acquired in themselves no fixed place in his ‘dynamic philosophy’. (Notes 3.3606)3

To say that they “acquired in themselves no fixed place” should read—since it is not that they don’t hold logically together (as she admits “What they denote was integral in his thinking”)—that there is no present third term or sign or vantage point (the Peircean “interpretant”) that reveals these terms’ relation to each other—that is, re-values them.

In this paper’s ficticism, then, Coleridge’s ideas are for us heuristic more than historic so that while attempting to respect the syntactic structures and forms of their arguments, we realize that in the new contexts of today, those older ideas that do in fact remain powerful do so not just as exemplars or because they somehow anticipate or influence directly contemporary ideas but because their syntax or forms are capable of carrying new meaning beyond the horizon for which they were originally intended. That is, some ideas are so constructed that they allow themselves to be reinterpreted in new and exciting ways.

3 Modeling Language, Thought, and Action

Therefore am I still

A lover of the meadows and the woods,

And Mountains; and of all that we behold

From this green earth; of all the mighty world

Of eye, and ear,--both what they half create,

And what perceive.

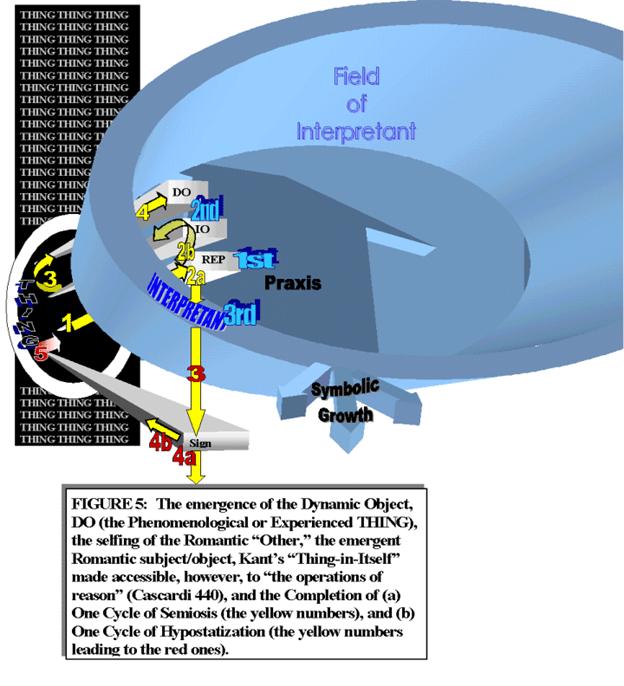

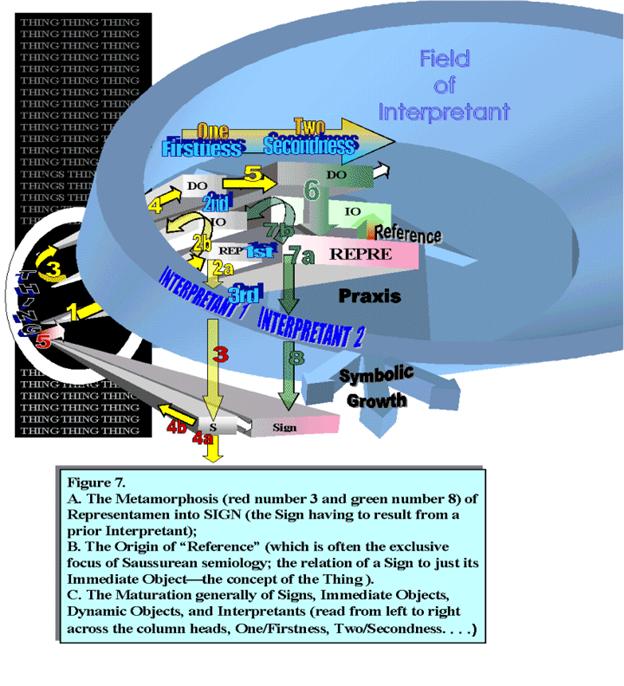

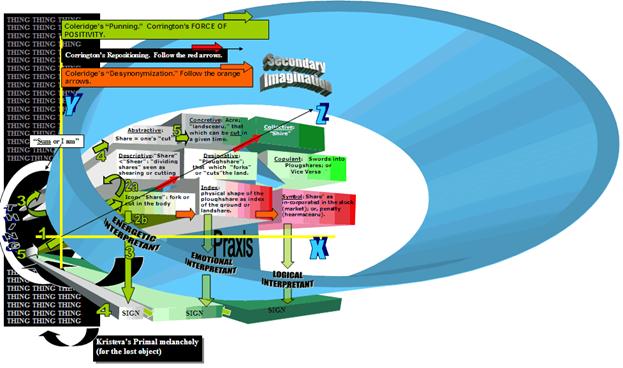

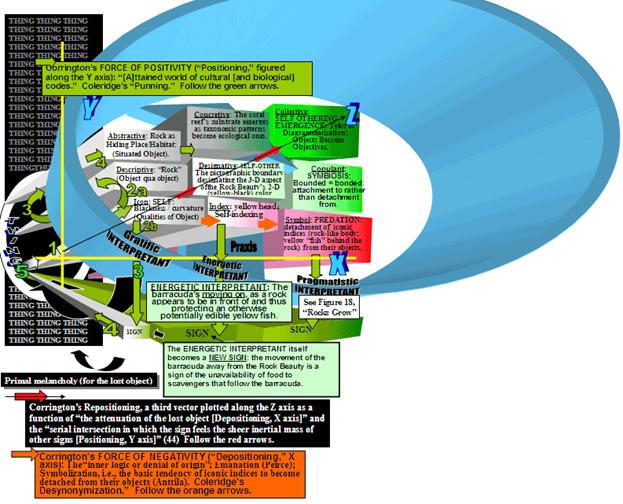

What Coleridge-“renewed”-through-Peirce offers is a precise way of understanding the dynamics of this famous but often loosely understood “half create / And what perceive.” In fact, Figure 1, “The Peircean Basis for a Formal Alliance Between Romantic Interiority and Material Reality,” may be understood as a formal/material model of the epistemological concept embodied in Wordsworth’s famous passage—ultimately, it forms the theoretical underpinning for our understanding of Figures 17 and 18 and the intentionality of rocks. Figure 1, and its seeming complexity, will be rendered much more accessible by viewing Figures 3-7, figures that represent the semiotic process of which Figure 1 represents a kind of unavoidable hypostatization. We should mention, however, that while some of the language to follow is, perhaps unavoidably, quite technical, it is our hope that our models may still be useful to a wide range of readers even as aesthetic renderings of, or arguments for, the imbricated nature of cognitive and ecological processes; one may overlook many of the terms and still get a feeling for the nature and the Nature of the environmental mind.

Figure 1, then, represents the following imbrications: in general terms, it represents (through Coleridge and Peirce) our understanding of how the world of sense creates the mind (“what perceive”) at the same time that the mind creates the world of sense (“half create”); in more specific terms, it represents

A. A“single” act of Peircean (and, in Figure 2, an act of Coleridgean) perceiving and knowing (and some of its ramifications) understood as (1) a recursive set of semiotic cycles leading to an emerging (i.e., an increasingly hypostatized) “solid” truth and a sense that “solid truth” arises, “flower-like” as the diverse or differentiated product of the evolutionary lineage of each arising sign—a profusion of signs that act on and are acted upon by the world/mind as they become more and more mature or as they generate more and more copies of themselves (Read "One," "Two," or "Three" across the column heads). Figure 17 gives an example of this emergence in terms of the appearance (or disappearance) of the surface morphological features of a prey species (the Rock Beauty) both over evolutionary time and within the phenomenological space-time continuum of the predators of that prey species. These “morphological features” are signs (or thought-signs with respect to the readers of the surface or textual body of the Rock Beauty [Figure 15]) and emerge in ways analogous to the emergence of words (signs) in Coleridge’s intertwined processes of desynonymization and punning. Predators of the Rock Beauty (like any readers) either are fooled by (innocent of) or solve (unpack) the complex visual puzzle that is their prey (text). Figure 1 also represents

B. The unfolding of two interwoven triadic modalities designated as (1) 1stness, 2ndness, and 3rdness and (2) One, Two, and Three. These two triads represent, from different points of view, the emergence of a given sign as a 1st or One (a “quality”), as a 2nd or Two (a “fact”), and as a 3rd or Three (a “law”):

1. The first and fundamental triad is embodied in the emergence of Peirce’s elemental Sign or Representamen (R), a Peircean 1st, as it unfolds into its Immediate Object (IO), a Peircean 2nd, and into its Interpretant, a Peircean 3rd. The Interpretant, the proper significate outcome of the Representamen or Sign, reifies the R-IO relation as well as presides over the emergence of the Dynamic Object (DO) This represents, as we shall see later, one cycle of semiosis. (again, read 1st, 2nd, and 3rd within Column “One”; see Figure 5 for a clear view of these elements). Once this initial triad emerges (as Column “One” itself), each triadic element itself is capable, according to Peirce, of a three-fold unfolding: Columns “One,” “Two,” and “Three.”

2. This second unfolding or maturing of the various signs is illustrated in Figure 1 by the slow spelling out from left to right from column to column of the names of the parts of the triad: Representamen, Immediate Object, and Dynamic Object. For example, the maturation or unfolding of the Representamen is captured in the transformation of that sign from a quality (say, a feeling of sharpness [column One]), to a fact (a knife! [column Two]), to a law (I won’t stick my hand into the dishwater so quickly again! [column Three]).

As we shall see,

both Peircean and Coleridgean semiosis represent a way of envisioning the

Kantian “Thing-in-itself” as materially “accessible to reason” (not just to the

“understanding”) and, in fact, as rendered more real through such accessibility.

Indeed, in the emergence of what Peirce calls the “Dynamic Object” (Figure 1,

the top row, left to right) and Coleridge the “Objective of Attention”

or “Reality” (Figure 2, the top row left to right), we discover the heart (the

body) of Coleridge’s goal of showing how sense may be derived from the

mind. Indeed, as Robert S. Corrington writes,

Peirce distinguishes between the dynamic and immediate objects. He uses this distinction to rewrite the Kantian distinction between the thing-in-itself and its phenomenal appearance under the conditions of sensibility and understanding. The dynamic object is analogous to the thing-in-itself, with the important difference that it becomes slowly manifest through time as inquiry proceeds toward truth [a process represented by the left to right exfoliation of the models in this article]. The immediate object is that side of the object that is always available to us at a given time [and, as such, our mental concept of the object, that side of the object that is immediately accessible to contemplation]. (80).

Before coming back to Figure 1, let’s look at Figure 3, “Representamens Arising from the Presemiotic Realm of POTENCY to the Semiotic Realm of the SIGN,” an early stage in the semiotic process or series of cycles that has led to Figure 1. Michael Haley,5 one of the collaborators in the project for which this essay is a kind of preliminary report, describes in his own terms his understanding of the first full cycle (which begins with Figure 3) of Peircean semiosis; this description roughly parallels the process as depicted in Figures 3-7:

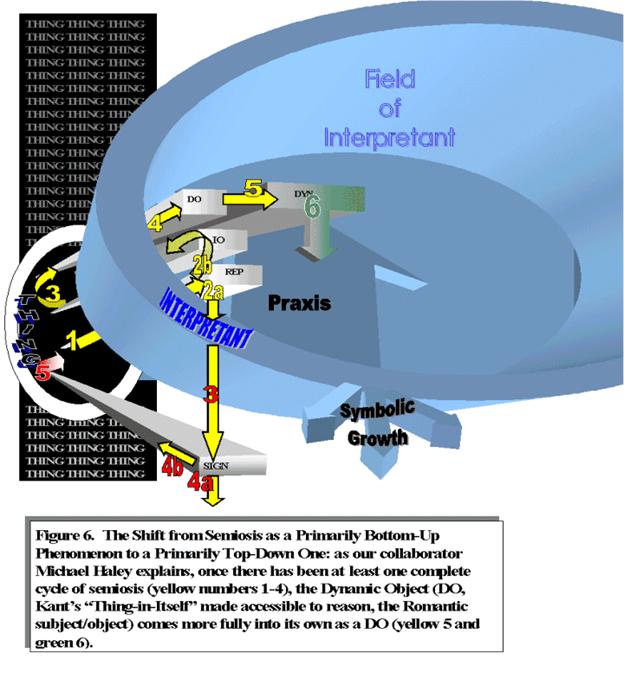

If I could illustrate the system as an animation, it might start out like this: A circle with a bunch of fuzzy things floating around in it. One of them starts getting jostled about more than the others and starts to glow and pulsate. It suddenly shoots out a ray-like [beam] . . . , at the [blunt end of which] a Sign [a Representamen] simultaneously springs into existence [Figure 3]. The [Representamen pulses] and sends out two additional arrows simultaneously [2a and 2b] [Figure 4], one [2a] straight outward to an Interpretant and the other [2b] circling back toward the original Thing. On its way back, this second arrow creates (and passes through) the faint shape of an Immediate Object, and when the arrow finally reaches the original Thing, Thing morphs into a Dynamical Object, albeit also a faint one [Figure 5]. In the meantime, the new Interpretant is sending out three arrows [Figures 4-7]: One (labeled “Symbolic Growth”) straight outward into ongoing semeiosis, one (labeled “Reference” [on Figure 7]) [point]ing back through the Sign to the Immediate Object (whereupon the IO becomes brighter and bolder), and the other (labeled Praxis) [point]ing back through the Sign to the Dynamical Object (whereupon it, too, becomes bolder and more definite). This would represent one full cycle of semeiosis. (3 June 2000)

Returning to Figure 1, we see that steps 1-7a/7b represent one cycle of semiosis beginning with the creation of an initial Sign hypothesis [Representamen, R] about a Thing, an Immediate Object (IO), and a Dynamic Object (DO). Each subsequent cycle from left to right plays out new but related hypotheses first about the Thing and then about the surrogate or phenomenal Thing, that is, about the Dynamic Object, as the Representamen and Immediate Object undergo hypostatization. Yellow numbers 1-2a and red numbers 3-5 [on Figure 1] represent, in Peircean fashion, another but related cycle of semiosis leading to the creation of a new sign; this cycle may recur infinitely (red 4a). Note how once the Interpretant comes into existence it forms a field (a blue collar or cone) that mediates all subsequent semiosis. More precisely, this Interpretant field, as our collaborator Mike Haley writes, 1. ratifies or validates the REPRESENTAMEN-OBJECT relationship, revealing it for what it is; 2. keeps OBJECT and REPRESENTAMEN from collapsing into each other; 3. contributes to the actual emergence of the REPRESENTAMEN; and 4. keeps OBJECT and REPRESENTAMEN connected in ways that can be examined critically (28 June 1999). As we shall see in Figure 2, the Coleridgean Symbol (or, what he sometimes calls in this functional context, the Representation, and in most other contexts, the Secondary Imagination) functions in much the same way as the Peircean Interpretant. A feeling for (if not a precise sense of) how the Interpretant field functions might be gotten from Coleridge himself in “Dejection: An Ode”: “Ah! From the soul itself must issue forth / A light, a glory, a fair luminous cloud / Enveloping the Earth-- / And from the soul itself must there be sent / A sweet and potent voice, of its own birth, / Of all sweet sounds the life and element!”

Getting back to the first of the two parallel semiotic cycles described above, the process represented in Figure 6 by number 6—the emergence of the Dynamic Object as a semiotic agent substituting for Thing, or, rather, the Thing become more and more real in a phenomenological sense—represents the fact that when some Thing has already been represented in a Sign there is an increase in the likelihood of its getting picked up and represented in more and larger signs. This fact, we have intimated already, is a key to understanding the accessibility of the Kantian “Thing-in-itself” to Coleridgean and Peircean reason, about which accessibility Anthony J. Cascardi writes, “many critics share the opinion that the most troubling aspect of Kant’s thought lies precisely in the claim that things-in-themselves are knowable by the understanding but remain inaccessible to the operations of reason, which must proceed by sense impressions” (439). As we shall see in Figures 17 and 18 (two versions of “Rocks Grow; or Objects Become Objectives. The Emergence in Terms of Peircean Semiosis and Coleridgean Desynonymization and Punning of a ‘Rock’ as a Web of Signing Actions or as an Object Growing into Objectives”), “the operations of reason, which must proceed by sense impressions” necessarily entail that what can be sensed is changed by the sensing—both over evolutionary time as well as through the interactions of the moment of the semiotic web. To predators of the Rock Beauty and their commensals, animal and human alike, (a) the rockiness (DO) of the Rock Beauty, (b) the emergence of the presence of an (imaginary) yellow fish (another DO) from out of the body of the Rock Beauty, (c) this yellow fish’s being perceived as if it were behind the emergent rock of what is in fact its own body (another DO), and (d) the decision to attack the Rock Beauty or pass by the securely hidden yellow fish all represent the shaping power of the sensed thing within eco-logic, that is, within a rock’s escaping from its inorganic realm and getting itself written into the reasoned codes of biological, aesthetic, ethical, and legal codes. In this example as it is explained in Figures 17 and 18, we shall see a precise Coleridgean and Peircean rendering of the Humboldtian logic of how, to paraphrase and adapt Malcolm Nicolson) emotional and aesthetic responses to a natural phenomenon (as well as the responses of a natural phenomenon to itself) can count as data about that phenomenon (or as feedback in its development).

Figure 6, then, highlights the shift from semiosis as a primarily bottom-up phenomenon to a primarily top-down one: as our collaborator Michael Haley explains, once there has been at least one complete cycle of semiosis (yellow numbers 1-4), the Dynamic Object (DO, Kant’s “Thing-in-Itself” made accessible to reason, the Romantic subject/object) comes more fully into its own as a DO (yellow 5 and green 6). It gets isolated, picked out from mere Things, by Praxis. If the Immediate Object is generally to be understood as a mental concept of a Thing (or some un-mediated and thus “im-mediated” relationship between an Object and its Sign), the Dynamic Object is the Thing coded as a discrete package of distinctive qualities and possibilities (only SOME of which have so far been actualized by the Representamen/Sign into an Immediate Object). Indeed, the DO is, from a phenomenological point of view, more real than the Thing-in-itself, more real, that is, in the Umwelt (lived world) of a given individual. Again looking ahead to Figures 17 and 18 and their representation of the signing action of “rocks,” we might here mention that this is how an Object, or even an aspect or single character of an Object, say the curved silhouette of a spherical rock from the substrate of a coral reef, a thin linear boundary between foreground and back, becomes a kind of script or writing: that boundary marker (or Object) drawn from the coral reef gets itself written (in a curved/cursive manner) first as a rock-like silhouette (C-shaped, see Figure 15) on the surface of the body of a fish called the “Rock Beauty” and then, as an Object having become a Sign of Beauty for a human observer, as an Objective in human aesthetic and even legal codes—as when legal Objectives are drawn up to protect Objects, thus making them Subjects. In this manner, the original silhouette of the rock in its original reef setting achieves its own preservation through the preservation of the original reef of which it is now a part as an aesthetic or ecological Subject.

For Haley, then,

Once there has been at least one complete cycle of Representation, Signification, Reference and Praxis, the DO [Dynamic Object] comes more fully into its own as a DO [Figures 6-7]. It gets isolated, picked out from mere Things, by Praxis. In being more clearly defined as a discrete package of distinctive qualities and possibilities (only SOME of which have so far been actualized by the Sign into an Immediate Object), the DO becomes even more Dynamic. In short, semiosis not only reveals a DO as such, but it actually makes it even more of a DO! . . . . [O]nce this "determination" has been made and the "information" about the DO has emerged through signification, then the DO is now no longer an altogether "invisible hand." In being made pointedly visible by Praxis, it becomes even more semiotically Dynamic.

Here's one way to think of how that might be: Peirce believed that there are two media in which possibilities get actualized. One is the medium of the natural world, the mind-external world of existent things and forces. But some possibilities, Peirce said, get actualized first in the mind of man, and pass through that medium secondarily into nature. Now, looking at [the] models, we can see that any possible DO's qualities have at least the potential of being actualized in the first way. Once the possible DO gives rise to any representation and signification, it has achieved some measure of actuality. But when the full cycle is completed in (conscious) Reference and Praxis, it is readily apparent that the DO's potential has now been actualized in the second way, as well. In other words, any DO that winds up being the target of Praxis has been double-actualized. That calls attention to even more semiotic potential in it, thus making it even more Dynamic. Incidentally, Peirce had yet another term for the Object presumed to lie at the limit of an "endless series" of such "representations" – the "Absolute Object." It would be the target of [the] black Praxis arrow, I presume, emanating from a Final Interpretant. It would be super-dynamic, presumably, super-actual, and super-real. (18 May 2000)

Again, Peirce’s Dynamic Object seems to suggest the ways in which Reason might be understood to access the Kantian thing-in-itself. Indeed, in Figure 7, steps 7a/7b represent the next cycle, which begins now from top down rather than bottom up in a key semiotic topographical shift consonant with the Dynamic Object’s evolving role in Peircean semiosis (as we shall see, there is a parallel step in our model of the operation of the Coleridgean symbol). At the same time, the process indicated by the red number 3 is that whereby the Interpretant itself becomes a sign that has the whole previous Representamen-IO-DO complex as its Object, and so on.

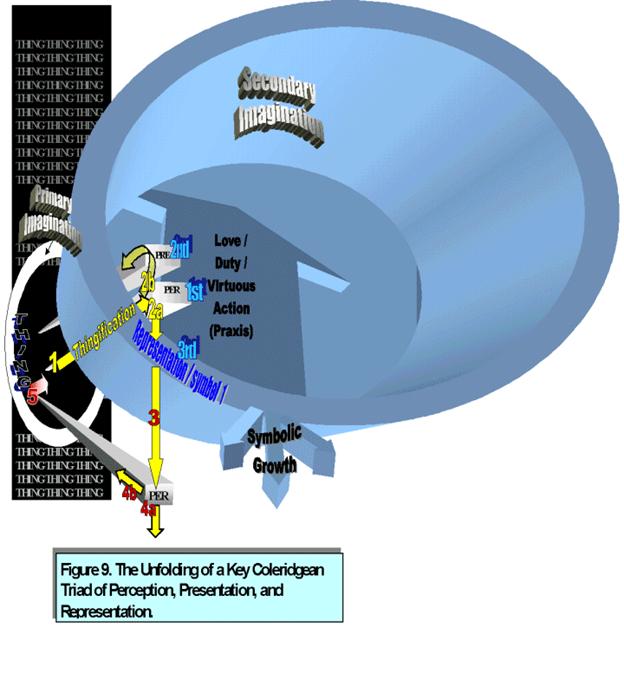

Figure 2, “A Peircean Model of Coleridge’s Realist

Solution to the Problem of How Sense May Be Derived from the Mind,” uses the

Peircean architecture of Figure 1 as its own iconic and indexical blood and

skeleton. (Robert S. Dupree was the first to articulate in print the striking

general parallels between not only Peirce’s and Coleridge’s thinking but

between their lives6; in what follows, we present what we have

subsequently found to be the striking similarities in some of the details

of their work on signs or symbols.) Of central interest is the manner in which

what Coleridge calls “Reality” or the “Objectives of the Senses” (at

this point in the semiosis of perceiving and knowing the equivalent of Peirce’s

Dynamic Object) are called out of “Duty,” constituted in “Love,” and generated

in response to “virtuous action” (Notebooks 2.3026) rather than

being understood as the merely referential objects or givens of some set of

signifiers—which function Coleridge relegates to “Fancy” and Peirce to

“Reference” (see the parallel placement of the arrows representing these

functions in Figures 1 and 2). “Duty,” “Love,” and “virtuous action,”

then, are the equivalents of Peircean “Praxis,” that is, those actions or

significate outcomes that constitute the combined effect of the Interpretant

field described above (see the large blue arrows and conical fields of Figures

1 and 2). What is for Peirce the field of the Interpretant is for Coleridge

the Secondary Imagination; see Figure 8 for a clear if brief depiction and

description of Coleridge’s “Primary Imagination.”

The larger passage from which the above terms of Coleridge are drawn clearly presents Coleridge’s view of the constitutive nature of “Duty,” “Love,” and “virtuous action”: “Reality in the external world [is] an instance of a Duty perfectly felt . . . Love a sense of Substance/Being seeking to be self-conscious, 1. of itself in a Symbol [which we align with Peirce’s “Firstness”—“quality”]. 2 of the symbol as not being itself” [which we align with Peirce’s “Secondness”—“fact”]. [and] 3. Of the Symbol as being nothing but in relation to itself--& and necessitating a return to the first state . . . [which we align with Peirce’s “Thirdness”—“law”]” (Notebooks 2.3026). Here then is a Coleridgean triad with clear Peircean parallels. In addition, as Robert Dupree first mentions and we illustrate in Figure 2, Coleridge’s Fancy, Primary Imagination, and Secondary Imagination represent a second parallel triad within Peircean semiosis (104).

The other Coleridgean terms that we have substituted in Figure 2 for each Peircean function have been supplied from his Notebook entry of August-September 1809. In this entry Coleridge attempts to outline his “Systems of Empirical Philosophy, or the Theory of the Syncretists.” Coleridge writes,

The sensitive faculty is the power of being affected and modified by Things, so as to receive impressions from them. The Quality of these Impressions is determined partly by the nature of the sensitive faculty itself and its organs, and partly by the nature of the Things. These impressions are in the first instant immediate Sensations: as soon as the attention is directed to them, and they are taken up into the Consciousness, they become Perceptions. The repetition of past Perceptions in the Consciousness is Imagination. The Object of the Attention during Perception may be aptly termed Presentation, during Imagination a Representation. (3.3606)

What is remarkable about this passage is its anticipation of some of Peirce’s key semiotic insights. For example, Coleridge like Peirce makes the distinction between Thing and Object, Object being the Thing after it has been taken up in experience. Coleridge like Peirce also distinguishes between what Peirce calls the Representamen (Coleridge’s Immediate Sensations, of which, as does Peirce, he speaks in terms of “Quality,” anticipating Peirce’s “Firstness”) and the Sign, what Coleridge calls “perceptions,” the immediate sensations once “the attention is directed to them, and they are taken up into the Consciousness.” Once this distinction is made both Peirce and Coleridge make another key distinction. For Peirce, once a sign arises in the mind both an Immediate Object and an Interpretant are created. In fact, an Interpretant is the proper significate outcome of a given signing action; indeed, a sign is a sign only by virtue of its having produced some outcome separate from the income: the relation of the Object to the Sign, or, the indebtedness of the Sign to the Object. For Coleridge, similarly, “as soon as the attention is directed to [immediate sensations], and they are taken up into the Consciousness” and become “Perceptions,” then, as Coleridge points out in the syntactic symmetry of his phrasing, “The Object of Attention during Perception may be aptly named a Presentation, during Imagination a Representation.” That is, just as for Peirce an IO (the mental conception or referent of a Sign) originates in the arising of the Sign, what Coleridge calls the Presentation represents perceptions (signs) attended to; at the same time, what Peirce calls the Interpretant, the proper significate outcome of a sign—as distinct from its reference to an immediate object or mental conception, Coleridge calls a Representation—the “Object of Attention” “during Imagination.” Though the symmetry of Peirce’s Interpretant and Coleridge’s Representation is not perfect, the force exerted by the Coleridgean Imagination on the Object of Attention that results in the “repetition of past perceptions” understood as “Representations” has parallels with the force exerted by the Peircean Interpretant. For Peirce, an Interpretant is an outcome, that is an effect or new sign of an earlier one—a form of representation in that the original sign re-presents itself as some outcome, but the Interpretant then serves to mediate or ratify or validate the Sign-Object relationship, to contribute to emergence of the Sign. Similarly for Coleridge, the Imagination calls out the repetition and representation of the original Sign/Perception.

In summary, Figure 2 depicts

A. A logical and chronological representation of the Coleridgean processes of Thingification, Synonymization, and Punning—an attempt at formalizing “a productive irreducibility that sustains Romantic subjectivity at a moment in cultural history when the signs of materiality were very much ascendant” (Kelley 4). Mind (Primary Imagination, Secondary Imagination, Fancy) and world are shown here not as binaries reducible one to the other but, rather, as emergent phenomena caught up in a three fold process: in Coleridge’s triadic terms, we observe “Substance/Being seeking to be self-conscious, 1. of itself in a symbol [a Peircean 1st—see the turquoise 1st above]. 2. of the Symbol as not being itself [a Peircean 2nd]. [and] 3. of the symbol as being nothing but in relation to itself—& necessitating a return to the first state [a Peircean 3rd]” (Notebooks 2.3026). (Read 1st, 2nd, 3rd within column “One.”) Note how the Coleridgean “Representation” or “Symbol” occupies the same encompassing position as Peirce’s “Interpretant” and generates a similar semiotic force field (the blue “cone”).

B.

A “single” act of Coleridgean perceiving and

knowing understood in the context of the long-term, diachronic, and intertwined

processes of “Desynonymization” and “Punning,” that is, understood as a

recursive set of semiotic cycles leading to an emerging (i.e., an increasingly

hypostatized) “solid” truth (Coleridge’s “Phænomena,” “Reality,” or “Objectives

of the Sense”) and a sense that “solid truth” arises, “flower-like,” both

through Coleridge’s “Desynonymization,”

“Punning,” and “Thingification” (Peirce’s symbolization, diagrammatization, and

the emergence of the dynamic object) AND as

the diverse or differentiated product of the (from our perspective Darwinian) lineage of each arising sign—a profusion of signs that act on and are acted

upon by the world/mind (“Divine Logos” for Coleridge) as they become more and

more mature or as they generate more and more (divergent) copies of themselves

(Read "One," "Two," and "Three" across the

column heads). Figure 14 illustrates one extended Coleridgean example of this

recursive or emergent maturation from “One”-ness to ”Three”-ness

in its tracing of what was originally a single sign into what becomes a

semiotic web of signification of partly arbitrary and partly motivated

linkages.

Figures 8-12 represent the folding and unfolding of Figure 2 in such a way as to illustrate the parallel dimensions shared by Peircean semiosis and Coleridge’s theory of the symbol.

Figure 12 represents the penultimate step in the semiosic cycle represented in its entirety by Figure 2. It is important because it highlights the shift from a bottom-up (perception driven) to a top-down (symbol-driven) model of knowing, but only when “symbol” is defined, as Raimonda Modiano tells us of Coleridge, as an “object”—as a material sign not unlike Peirce’s Dynamic Object. As Modiano writes, summarizing Coleridge’s thinking, “What man desires most is a symbol which in a sense is bigger than itself, is more than a symbol, i.e., an object which is at once the mind’s ‘Symbol, & its Other half’” (73); again, not a bad definition of the Peircean Dynamic Object.

Figure 12 is

important also because it illustrates that once Thingification (the

creation of the “Objectives of Sense”) has completed one full cycle, the

repetition of each subsequent cycle represents for Coleridge two processes

simultaneously: Desynonymization and Punning—both of which patterns represent

the “telos of diagrammatization,” a carving out of new semantic space

understood as either linguistic branching or webbing. Coleridge writes,

“Imagination = imitation or repetition of an Image” (3.3744;

translation by Kathleen Coburn). When

such repetition is not only of past perceptions but of re-presentations (a

repetition of a repetition or presentation of a presentation), then we have not

only Wordsworth’s reconstitutive power of memory, of the past for the present,

but of the constitutive power of the present for the future. As Coleridge

writes in a passage cited earlier, “The repetition of past perceptions in the

consciousness is Imagination. The Object of Attention [the “THING”

experienced] during Perception may be aptly termed Presentation, during

Imagination a Representation.” Here, Presentation is the equivalent of

Peirce’s Immediate Object (the Object of Attention in its immediacy, its

unmediated relation to consciousness). However, under the Secondary Imagination,

the Object of Attention is re-presented, in an act of mediated Perception that

creates not a referential relationship between Percept (sign) and the mental

image of the thing but the effect, the outcome, that that prior referential

relation produces in the mind or the world. This effect or outcome is the

equivalent of Peirce’s Interpretant, the proper significate outcome of any

referential (that is “sign-object” or “perception-presentation”) relationship.

This repetition of past perceptions to produce a present-ation gives way

under the Secondary Imagination to a repetition of the re-presenting of

the present, the presentation of an altered version of the present or a significate

outcome rather than a specific meaning. The Secondary Imagination (in Figures

2, 9-12, and 14, the blue cone within which signs grow) represents a secondary

repetition. At this level, repetition is not merely redundant or

self-reflexive but rather generative of new lexical niches (desynonymization)

or webs (punning).

Figure 13 represents another set of Peircean terms or functions with which we describe in more detail than did Coleridge himself one of his favorite examples of desynonymization and punning (again, see Figure 14). Figure 13 illustrates, as do Figures 1-12, the relationship between (and the unfolding of) two Peircean, interwoven triadic modalities. What is different here is that what is the “Representamen” or “Perception” in our Peircean and Coleridgean models is now a “Qualisign” or “Icon,” terms that for Peirce designate, respectively, a sign as a Quality or a Resemblance. Figure 13, then, shows the unfolding of Qualisigns and Icons into a semiotic (and taxonomic) fullness that was before represented merely by the gradual spelling out from column ONE to THREE of terms such as Representamen, Immediate Object, and Dynamic Object—which gradual “spelling out” represented the general sense of their maturation. In Figure 13, however, we see that signs mature in very precise ways: Peirce’s Representamen or Sign function unfolds as Qualisigns become Sinsigns become Legisigns; the IMMEDIATE OBJECT unfolds as Descriptive signs become Designative signs become Copulant signs; and the DYNAMIC OBJECT unfolds as Abstractive signs become Concretive signs become Collective signs. Note also the threefold classification of Interpretants (“proper significate outcomes”) as Energetic, Emotional, and Logical. These three types of Interpretant, though their meanings are quite clear just from their names, will be made clear in their effect in Figure 18 where each is seen as an emergent character of a rock/Rock Beauty.

The above Peircean terms serve, even without knowledge of their precise technical meanings (the knowledge of which is not our goal here), a kind of heuristic function even if we consider only their generic or etymological meaning. Figure 14 may be understood as tracing in explicitly Peircean terms Coleridge’s own example of semantic growth: that involving “Share,” “Plough share,” and “Shire,” “three Synonimes so perfectly desynonimized” (Notebooks 2.2432). The X-Y-Z axes of Figure 14 represent a field within which punning and desynonymization may be seen in interrelated and emergent terms. Coleridge’s own three examples fit nicely into the Peircean matrix that his own theory of the symbol clearly anticipates.

Figure 14 is important because it suggests, in its close affinity with Figure 17, how conscious socio-linguistic change (and Coleridge was certainly a proponent of the role of consciousness in developmental models of change) is not essentially different from that which underlies unconscious natural semiosis—a view held by the Naturphilosophen but one with which Coleridge was not comfortable. Darwin, in the first two chapters of his Origin of Species (6th Edition), argues, of course, that human conscious selection in breeding is no where the equal of unconscious natural selection in evolution; indeed, had we time to go further into the point, the same might be said when applied to linguistic evolution on the one hand and the semiosis of nature (from DNA to coevolution and its production of such defense mechanisms as chocolate!) on the other. The process illustrated in Figure 14, then, is one whereby a word, such as “share”—which is based on a simple relationship of physical resemblance, such as that between the fork shape in the human body and a cut made by a “shear”—may be transformed into a whole host of linguistic and cultural units. As Anttila says, and as we quoted in the context of Shakespeare’s “salad days” and Freinkel’s Hamlet / Hamlette play/pun, “This is general in evolution. Units adapt to their environments by indexical stretching to produce an icon of the environment.” Whether the units are thought-signs, words, genres, species, or social structures, the isomorphisms highlighted by our models suggest that a renewal of our understanding of intentionality (of the roles of the conscious and the unconscious, of the interior and the exterior) is called for. Indeed, this is just the point we hope to illustrate in Figure 17, “Rocks Grow; or Objects Become Objectives. The Emergence in Terms of Peircean Semiosis and Coleridgean Desynonymization and Punning of a ‘Rock’ as a Web of Signing Actions or as an Object Growing into Objectives” and in Figure 18, “Rocks Grow; or Objects Becoming Objectives. A Semiotic Web of Being Based on Schelling’s Naturphilosophie and Coleridge’s Constitutive Theory of the Pun.”

4 Rocks Grow; or Rereading Intentionality

It is worth noticing that in the Scriptures, and indeed in the elder poesy of all nations, the metaphors for our noblest and tenderest relations, for all the Affections and Duties that arise out of the Reason, the Ground of our proper Humanity, are almost wholly taken from Plants, Trees, Flowers, and their functions and accidents.

Coleridge’s note in Copy G of Appendix C to The Statesman’s Manual]

As a necessary prelude to understanding Figures 17 and 18, let us engage in a close reading of the fish Holacanthus tricolor, the Rock Beauty (Figures 15and 16), keeping in mind the contexts described above that intentionality does not necessarily involve consciousness, that significance emerges and is sustained through “outness,” and that ideas are other-evident. Figure 15 reveals the Rock Beauty in its full lateral view. Figure 16 situates the Rock Beauty in its habitat: the coral heads and round rocks of the reef.

The body of the tropical marine fish called the Rock Beauty—considered with respect to its “outness” or intentionality, its desire to write itself out of its situation, or its effect on a human observer/predator or on a natural predator such as a barracuda—consists of three figures of sight, one of which is iconic, one of which is indexical, and one of which is constructed out of the relationship between the iconic sign and the indexical sign. The icons and indices of the rock beauty, though more often than not useful to the rock beauty as survival strategies of biological mimicry, may become (or be made into) detached and arbitrary symbols (and edible ones) if the rock beauty's predator solves the complex visual puzzle presented by the rock beauty.

The head and tail of the rock beauty are bright yellow (showing as white in the black and white reproduction provided); as indices generally do, the yellow head and tail call attention to themselves and also orient themselves (and any observer) spatially with respect to some object with which it is connected—see Peirce's indexical “weathercock” (2.286). In this case, the object is the Rock Beauty's own large, black midsection that breaks its body in two so as to appear to be in front of a yellow fish. This midsection is itself iconic of the spherical surface of a rock or a coral head. The boundary between the yellow indexical head of the rock beauty and its black iconic body roughly describes an arc of some 90 degrees; the arc itself is an icon of both the long-term effects of erosion, effects which produce spherically shaped rocks, and the sphericality of coral heads, which heads often form on round boulders anyway, providing a natural base for their spherical growth. Thus the yellow indexical head and tail and the circular arc described by the boundary between head and body are part of a single indexical and iconic sign complex. To predators of the rock beauty, then, the yellow fish appears to be behind the dark rock or coral head; this effect is heightened underwater when the rock beauty is seen against the dark rocks and coral heads of a reef, a reef that contains innumerable nooks and crannies into which prey species are frequently partially or fully withdrawn. In semiotic terms, then, the indexical head and iconic body of the rock beauty are signs that determine the interpretant, i.e., the mind of the predator, to refer to the (imagined) all-yellow fish as if it were behind an (imagined) rock; that is, the interpretant or predator is determined to refer to objects to which the indexical head and iconic body of the rock beauty themselves refer. As Peirce writes, “A Sign is anything which is related to a Second thing, its Object, in respect to a Quality, in such a way as to bring a Third thing, its Interpretant, into relation to the same Object, and that in such a way as to bring a Fourth into relation to that Object in the same form, ad infinitum” (2.92). Given the feigned inaccessibility of the rock beauty (a fish that is both Sign and in part its own Object), the rock beauty's predator (say the barracuda) may itself be brought into this relation of inaccessibility and move on to more accessible prey, of which there are many in a reef; this moving on is an interpretant of the sign-object relation. Other predatory fish, Fourths, may follow the barracuda's lead and move on as well. In this sense the barracuda is a Peircean Interpretant not a generalized interpreter; its moving on is itself a sign in a new web of primarily ecological signification that is a reef community.

The Rock Beauty's predator, however, could also solve the complex visual puzzle presented by the rock beauty, effectively detaching from their objects the Rock Beauty's iconic and indexical signs and thereby changing the status of those signs from motivated icons and indices to unmotivated symbols (thus bringing about the “perception catastrophe” of which René Thom [61] speaks). This detachment of icons and indices from their objects and the resultant production of arbitrary symbols is at the heart of the evolution of syntax and predication (Coletta 223).

Figures 17 and 18 attempt to represent the above-described process in the diagrammatic terms of Peirce and Coleridge. In Figure 17, we see illustrated how a Thing, even an aspect or single character of an Thing, say the curved silhouette of a spherical rock from the substrate of a coral reef, a thin linear boundary between foreground and back, becomes a kind of script or writing, as that boundary marker (or Thing) drawn from the coral reef gets itself written (in a curved/cursive manner) first as a rock-like silhouette (C-shaped, see Figure 15) on the surface of the body of a fish called the “Rock Beauty” and then, as an Object having become a Sign of Beauty for a human observer, as an Objective in human aesthetic and even legal codes—as when legal Objectives are drawn up to protect Objects, thus making them Subjects. In this manner, the original silhouette of the rock in its original reef setting achieves its own preservation through the preservation of the original reef of which it is now a part as an aesthetic or ecological Subject. Start by reading the cell that reads, “Icon: SELF: Blackness / curvature (Qualities of Object),” in the lower left-hand corner of the area within the blue cone. These qualities of the underwater rock, “qualisigns” as Peirce calls them (see the same cell in Figure 13), may then be seen to generate the semiotic and ecological web of the whole of Figure 17.

Figures 18, “Objects Becoming Objectives,” gives

another view of the same process illustrated by the natural visual punning

described in Figure 17. Again, Figure 18 combines Coleridge’s constitutive

theory of the pun, his “desynonymization” (which is the linguistic equivalent

of Anttila and Peirce’s “symbolization,” the idea that icons and indices tend

over time to get detached from their objects and become conventional symbols),

and his view of the linguistic structure of nature with the dynamic view of the

self-organizing nature of Nature of the Naturphilosophen. As we have

mentioned, Coleridge captures this emergence in his own visual “pun,” one that

results from his erasure or crossing out of part of one word only to reveal two

words simultaneously. Coleridge connects “objects” to “objectives” in a

phenomenological manner when he writes, “The Objectives of the Sense are

collectively termed phænomena” [Notebooks, 3.3605]). A modern semiotic world view combines the Naturphilosophen’s

sense of the self-organizing, symbolic nature of nature as capable of ‘”becom[ing]

an object to itself” (Modiano 164) with Coleridge’s similar sense that the pun

is an iconic force for the motivated linkages that drive the evolution of the

lexicon: As Coleridge writes on his “intended Essay in defence of Punning,”

“Language itself is formed upon associations of this kind . . . . that words

are not mere symbols of things and thoughts but themselves things’ (Notebooks

3.3762). In Figure 18, we see nature as an unfolding Coleridgean pun structure

whereby an “object” becomes an “objective” and an icon of a “rock” becomes

again the rocky substrate from which it emerged; that is, observe how a

pun structure underlies the constitution of natural linguistic signs as well as

the “intentional reach” of a rock as it gets itself written into a whirlwind of

biological, aesthetic, and moral codes (Interpretants) and ultimately works to

get itself preserved (indirectly) in the preservation of the substrate of the

reef of which it is a part: we preserve the reef substrate so as to preserve

the things of beauty, the Rock Beauty, the rocks, that are in it—that reach out

to us. Remember that in reading Figure 18, “Interpretant” for Peirce refers to

the proper significate outcome of any sign-object relationship (not referential

meaning).

In Figure 2 we attempt to translate into a biological context, and using the semiotic terms of Charles Sanders Peirce, Coleridge’s provocative thought that “Reality in the external world [is] an instance of a Duty perfectly felt . . . Love a sense of Substance/Being seeking to be self-conscious” (Notebooks 2.3026). In Figures 2 and 18 we attempt to show how, in the spirit of Naturphilosophie and its belief that “nature becomes intelligible and approaches the life of reason only as an activity by means of which it becomes an object to itself” (Modiano 164), that what Coleridge ascribes to “Being” is also true of any entity, living or otherwise.

5 “Outness” of Mind

Figure 18, it seems to us, suggests how the emergence of thought-signs and interpretants in human cognition differs from the signing action of nature only in the former’s having had its emergence rearticulated in terms of a digitally rendered and infinitely accessible concentration of things along an equally concentrated continuum of time and space, while the signing action of nature carries on in accordance with the slow but earnest analogue emergence of meaning as manifest in a universe, as Peirce would say, perfused by signs. Deceit, invention, metaphor, self-interest, irony, agency are all there in the signing action of nature.

In the following passage from his Notebooks (3.3324), Coleridge anticipates (indeed seems to experience physically) the artificiality of the distinction between “inner” and thus outer mind, a distinction that we too have tried to problematize in Figures 17 and 18. In the cited passage to follow, Coleridge appears to be somewhat uncomfortable with this not yet fully understood experience of mind and thought as not residing in the skull but rather somewhere in between. Nevertheless, Coleridge gives a remarkable experiential rendering of what is one of Peirce’s most abiding expressions: “[T]hat every thought is an external sign, proves that man is an external sign” (54), constituted by “COMMUNITY” (52). Coleridge writes,

My inner mind does not justify the Thought, that I possess a Genius—my Strength is so very small in proportion to my Power—I believe, that I first from internal feeling made, or gave light and impulse to this important distinction, between Strength and Power—the Oak, and the tropic Annual, or Biennial, which grows nearly as high and spreads as large, as the Oak—but the wood, the heart of Oak, is wanting—the vital works vehemently, but the Immortal is not with it—

And yet I think, I must have some analogon of Genius; because, among other things, when I am in company with Mr Sharp, Sir J. Mackintosh, R. and Sydney Smith, Mr Scarlet, &c &c, I feel like a Child—nay, rather like an Inhabitant of another Planet—their very faces all act upon me, sometimes as if they were Ghosts, but, more often as if I were a Ghost, among them—at all times, as if we were not consubstantial.

What justifies Coleridge’s sense that he has some “analogon of Genius” is not his “inner mind” but his community-of-friends’ actions upon him—which render him ghost-like. Here we have in human terms the analogue of the emergence, in Figures 17 and 18, of the ghost-like yellow fish behind the “rock” of its own body. Like that “fish,” Coleridge is himself a construction of his social environment or existence: “[Coleridge’s friends’] very faces all act upon him”; the face off between the Rock Beauty and its predators, the encounter and manufacture of the play of forms on the surface of the Rock Beauty and on the surface (the present) of the mind of the barracuda all act upon each other so as to pull the ghost of the rock out from its mineral essence into its semiotic being. In what is a clear anticipation of modern semiosis, meaning for Coleridge in this important passage is not an essence shared consubstantially but a ghost or trace; something construed by analogy (by similarity and difference), something that is always other to itself, and so Coleridge feels “like an inhabitant of another Planet” or a “Child”—the only analogon’s available to him of what we would call the postmodern self. In this passage, Coleridge’s vegetative image and the distinction between Strength and Power that it supports also anticipate present-day semiotic understanding of the sort represented by Figures 17 and 18. The “rock” of those figures, like a “tropic Annual, or Biennial,” has great (semiotic) powers of (emergent) expression—“the vital works vehemently” through it—as it gets itself written into, “grows nearly as high and spreads as large,” the neuronal tree structures of the brains of the predators of flesh and symbol, but there is little “wood,” or little of the “Immortal.” But “Immortality” is not a concern of ecological semiotics; rather, Immortality’s modest Other, “preservation,” is the telos of the rock’s and the “tropic Annual, or Biennial”’s power.

This passage is perhaps analogous in its effect, if nothing more, to those experiences that we’ve all had when saying the word “the” or some other very familiar word over and over again until, as Michael Haley writes, we experience “a kind of semiotic ‘computer crash’ (e.g., when . . . the consciousness of [the word’s] uniqueness as a sign seems to override its meaning, causing it to seem meaningless).” Coleridge’s passages ends with a semiotic ontological moment or “spot in space” wherein Coleridge experiences via a face-to-face encounter (indeed the face-to-face encounter is the very sign of a collapsing allegory of being) the opacity of the sign as signifier—its materiality and our subsequent immateriality—the recognition that meaning resides not in an essential inner idea but through externalized relations, the self being even an Other to the self, and thus a Ghost.

Here, then, in this passage from Coleridge’s Notebooks, is the experience of the disembodied mind for which we have been attempting to create, in the many models presented here, a pictographic and (eco)logical description of the environmental mind.

Notes

1Unless otherwise noted, we will present citations to Peirce’s work as is customary in Peirce studies: by citing the Volume and paragraph number from his Collected Papers.

2Citations to Coleridge’s Notebooks will include Volume and entry number.

3James C. McKusick’s Coleridge’s Philosophy of Language, New Haven: Yale UP, 1986, was indispensable to my analysis of punning and desynonymization, though any confusions on my part are derived fully from my own lapses.

4Citations to Kathleen Coburn’s Notes to the Notebooks will include Volume and entry number.

5Without Michael Haley (Professor of English at the University of Alaska-Anchorage) and his tireless mentoring, none of these models and their attendant ideas would have ever materialized.